This morning I am thinking about Edna St. Vincent Millay.

My poetry friends know I love Millay’s poetry. Some know I am in love with her, or at least with the imaginary crazylove ahistorical version of Millay that my mind conjures from her biographies, poems, and letters. My wife knows. No reason to be jealous or worried since Vinnie died shortly before I was born. I can visit with her only through her poems.

I have written elsewhere about Millay. My plea that you read what I wrote earlier is more for the remembrance of her own beautiful lines and poetic forms and her brave, tempestuous, self-created life than for my own freshman words about her.

In her poems, words flowered. Through the rest of this piece, I will offer Ms. Millay my own photographed flowers, poetry’s greatest metaphor for beauty and its fleeting ephemerality.

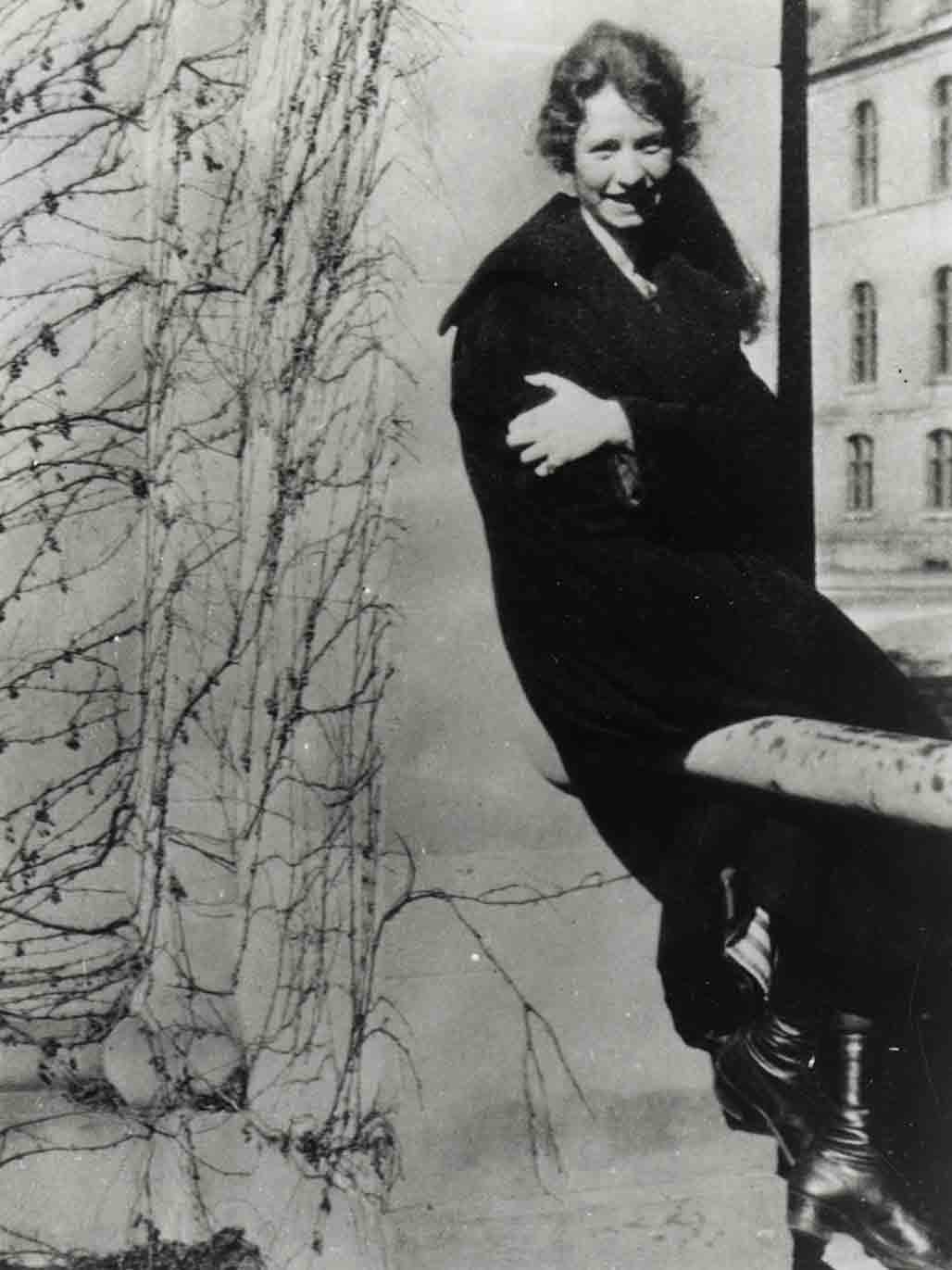

For me, reading Millay means thinking about Beauty, and about the elegance and sophistication of her lyric poetry and its craft, particularly her sonnets. But also her personal beauty, physical, noetic, and moral. Her sprite-like body and flaming red hair were matched by her sharp intelligence and wit. And there was beauty too in her outspoken moral and political stances. She never compromised how she lived, what she believed, or what she wished to write about or how she wrote it.

And reading Millay, of course I also think about Love, because she writes so frequently and penetratingly about it. I fall into a trap here: Millay has historically been pigeonholed by much literary criticism as the poetess-enchantress of the 1920’s bohemian Greenwich Village love scene, but there’s so much more in her work. Her Nature poetry stands up to any. She often treats of family, grief, politics, memory, childhood, feminism, and death. But Romance and Love, capitalized, are omnipresent as she probes, again and again, the secret regions of the heart.

Love

Millay was disparaged in her time by the academic and poetic elite (largely male) for writing about old verities like romance, popular they said among female poets, and doing so in traditional poetic forms like the sonnet, at a time the world demanded an art that was fragmented, experimental, philosophical, and impersonal. In her verse, she was no Modernist. Her poetry was, it was said by the emerging poetic upper crust, rooted in the past. The fact that she wrote with intensity, polish, and skill, and the fact that she lived defiantly, modernly, and unapologetically as a free woman poet in her moment, added nothing to her account.

Frankly the poets and critics who dismissed Millay at the time strike me as cold, sexless, and self-important. Who am I thinking of? Poets like Eliot and Pound (more on that in a moment), and influential critics like Allen Tate (Millay “did perceptible damage to our young American womanhood”, although Tate also said no one since Shakespeare had written love poetry as good as Millay’s, so go figure), John Crowe Ransom (what “the male reader misses in her poetry [is] her deficiency in masculinity”), and John Gould Fletcher (“wishy-washy to the point of intellectual feebleness”). Leave the great literary critic Edmund Wilson out of that intellectual rogue’s line-up, since he at least had the good sense to fall madly in love with her and propose marriage (declined).

Millay could write so movingly about love’s labor’s lost and found because she wrote what she lived. I think of her as being in love with Love, not narcissistically (well, OK, maybe) but experientially. In love with all Love’s aspects, its satisfactions, longings, aches, consummations, with the game, its good fortunes and defeats, with its playfulness and mischievousness, its secrets, its intoxications.

“Love is a smoke raised with the fume of sighs,” Shakespeare has Romeo say in Act 1, scene 1, ”Being purged, a fire sparkling in lovers’ eyes; / Being vexed, a sea nourished with loving tears.” But those are the words of a fictional character. Millay was very real, and in her heightened life she lived the deepest meaning of Shakespeare’s words.

Who wouldn’t want to know this person? Who of any gender wouldn’t want to be in her amatory orbit - that is to say, in her bed - even if just for a “little day”? In exploring the vicissitudes of crazy romantic love, only Millay has approached Shakespeare in showing over and over in a sonnet what it means to give everything to it. (We know nothing of Shakespeare’s own love life in London, away from Anne Hathaway in Stratford. But I think we can safely say that, of the two sonneteers, only Millay owned an ivory dildo, destroyed with some difficulty by her surviving sister after her death.)

In an article published on Medium titled “Wisdom from the Only Woman at Plato’s Symposium” (I highly recommend it, if you can access it), I learned how rich a vocabulary the ancient Greeks had to express the experience of love. Love is, variously, passionate, selfless, familial, flirtatious, practical, self-involved, respectful, and more. For each of these manifestations of love there is an ancient Greek word.

Millay explored the terrain. She explored personal experience, longing, deep feeling, all the facets of love, with psychological sophistication. Compare her to a poet enshrined by academia, the poète provocateur Ezra Pound. So enamored was he of the wisdom of classical thought that he managed to produce a sprawling magnum opus (The Cantos) and many other books of poetry, essays, and translations without ever once writing a love poem - that little matter in human affairs that the classical writers did not overlook.

Nor did he write a poem about Nature. He had no feeling for it. He was more interested - obsessed - with arete (excellence and virtue) and logos (reason) than love. Poetry extolling a subject like Love, no matter how enduring a theme, was sentimental and outmoded.

Something in Pound’s loveless deportment in and out of his poetry seems of a piece with his dark inhumane political fascism. Perhaps Millay’s engagements and affairs with humanity is what led to her more enlightened political stances — her very public fight against the Sacco and Vanzetti executions, her pacifism during World War I, her fight for women’s rights, and her direct (and costly) contributions in the fight against Nazism and fascism in World War II.

I will choose Millay over Pound every single day of the week, every single minute of the day. That’s Love.

Beauty

The ancient Greeks knew that, like love, Beauty is multifaceted. Thus, Beauty is seen in fleeting moments of perfection. There’s Beauty in moral attitude. There’s Beauty in harmony and proportion, and also in a sense of proper alignment. Long-term healthy flourishing is a kind of Beauty, as is its opposite, short-term hedonistic pleasure. Beauty is present in radiance and luminosity. Each manifestation of Beauty has its own word in old Greek. (Or so the internet tells me. I only speak English, and everything else, as they say, is Greek to me.)

"Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know."

That’s John Keats, or more precisely, that’s the Grecian Urn of ode fame speaking as “a friend to man.” Keats’ grand insight was inspired by an imagined urn of classical times, exquisite in its artistic beauty and brilliant in capturing a truth about the fleeting nature of joy and love, all the while sitting silently outside of time, atop (one imagines) a pedestal in the British Museum.

Is Truth and Beauty really “all ye need to know”? This is a wonderful High Romantic flourish, but the world is a mess, and you might need to know things like where your next dollar is coming from, what your evacuation route is, and who your friends are. But never mind all that. If truth and beauty happen to be all you know, you’re living a very good life.

Millay knew about more than Beauty, but she surrounded herself with it and wrote about it and created it.

Poetry

The poetry I seek out and favor always deals in some fashion with the big issues, the fundamentals, the universal, the heightened experiences that occur in our few moments on stage which are then expressed with the heightened resources of language. Beauty and Truth, yes, but all the other big ideas and insights, revelations and satoris, love, the natural world, spacetime, and God in whom I don’t believe but am happy to read about if the poet happens to be, for example, Gerard Manley Hopkins.

On the other hand, I’m decidedly not interested in something like “Ode to Armpit Hair,” a contemporary poem actually published in Poetry magazine that elevated Self over anything that matters. (The poem title is click-bait, compelling me to read the damned thing just like I might feel compelled while driving to look at a dead deer on the side of the road.

Carefully curated, poetry really can show us how to live a more meaningful life, or at least how to aspire to one. I actually believe that. Poetry, philosophy, and science are our greatest teachers, enhancing our own lived experiences and fortifying the lessons of actual teachers (in whatever guise) we are lucky to have met.

What has poetry told me? Wallace Stevens has floridly reassured me that poetry is the supreme fiction among the various “realities” we concoct for ourselves. I believe him. He shows how far the Imagination can take us in words and images. I am content with things upon his blue guitar. Emily Dickinson has allowed me to follow her incandescent mind “off the banks of noon” to transcendent places I would never have reached on my own. Whitman convinced me of our cosmic connection as we ferried from Mannahatta to Brooklyn. The ever-popular Mary Oliver (who lived for a while at Millay’s house with Millay’s sister) has reminded me, vividly and repeatedly, to wake up.

What has Millay offered me? In her poetry I feel the breathing presence of a woman who lived wildly and carelessly and always on her own terms, and then made poetry of matchless beauty from her experience. I admire her immensely for the tensile strength of her mind and opinions, for her uncompromising political values and actions as an adult with fame and influence, and of course for her rare, incandescent talent.

She has taught me the value of lyric poetry. She reminds me it is necessary for poetry to feel, not just mean and not just be. Because people feel. Because I feel.

She has sometimes been dismissed as a young person’s poet, or as a women’s poet. But I am neither a young person nor a woman, so what am I to make of that? Is she a women’s poet because she writes not in the impersonal, erudite style of a T. S. Eliot but instead with great unhidden emotional depth? Robert Lowell made confessional poetry into a genre based on his turbulent emotional life, but the last thing he can be called is a women’s poet. Is she a young person’s poet because she could write so movingly of childhood? Elizabeth Bishop wrote of childhood too but has not been relegated to such a restricted definition.

Millay was a sophisticated, stylish, and well-read artist (poetry, plays, and libretti) whose dismissal as a great American poet strikes me as nonsense rooted in either misogynistic attitudes, academic elitism, or both. What she wrote was loved or admired by real people, great and small, in America and abroad, and still is. The great British novelist and poet Thomas Hardy said that America’s two greatest achievements were skyscrapers and Edna St. Vincent Millay. I have some serious competition for Millay’s ardors.

In her dealings with men and women and with society, Millay could be impetuous, willful, passionate, difficult, defiant, vulnerable, imperious, selfish, confident, droll, theatrical, struggling, hurtful, hurting, and resilient. She was all these things in her poetry, too. Few people can live at such a level of intensity. And only the rarest can write that way.

Millay’s Greatest Love

Millay married well. Her husband Eugen Boissevain was a Dutch importer with money (she didn’t need it; she was the rare poet making plenty from her books and public readings) and a wide open attitude about marriage and love. Together they fled New York for their farm at Steepletop in rural New York where they threw bacchanalian parties, quietly gardened, cooked (he), and wrote (she). (There is a small wooden writer’s shed on the property, and lucky me, I stood in it as a visitor one Spring day. Vinnie wasn’t there, sadly.)

Millay deeply loved her mother and her two sisters. But she loved no one more than Eugen. He was her husband, her lover, and her caretaker, providing whatever she needed as a writer, or tolerating whatever she did as a free woman. When she became addicted to painkillers, he got himself addicted so that they could kick the habit together. Devotion has never been as crazy and steadfast and tolerant. He was her North Star.

Tolerance meant accepting Millay’s torrid love affair when, at the height of her fame, she fell madly - always madly - in love with a much younger American poet in Paris, George Dillon. Many of the sonnets in her 1931 volume “Fatal Interview” were inspired by their fiery affair, its careening instabilities, and ultimately its impermanence and end.

The sonnets achieve Shakespearean levels of intensity, insight, and craft. We don’t know whether Anne Hathaway ever read Shakespeare’s love sonnets to the Fair Youth, but we do know that Eugen read Edna’s and accepted that her affair with the young poet was channeled into lasting poetry.

Not for a moment did Edna and Eugen waiver in their dedication to each other. Their love admitted no impediments and bore them together “even to the edge of doom.” It was truly a thing of beauty. As for Dillon, with Millay’s poetic mentorship he won a Pulitzer Prize at age 25 for his lyrical poetry in “The Flowering Stone” but, after the affair crashed and burned, he never wrote poetry again.

The sonnets inspired by her mad crush and the mad end of the Dillon affair are among her finest. Go to Sonnet 2 (“Time does not bring relief; you all have lied”), Sonnet 17 (“You were my light a little while, my dear,/ A little while, my heaven and my star”), Sonnet 30 (“Love is not all: it is not meat nor drink”), and Sonnet 39 (“I know I am but summer to your heart”).

Some Poems

I am not going to discuss the sonnets of amor fou that Millay wrote in her wildchild college days or her bohemian life in New York. If you want to read her best about hateful Love, sweet love, faithless love, go to the links I just offered and here (“I, being born a woman and distressed”), here (“What lips my lips have kissed, and where, and why”), and here (“I shall forget you presently, my dear”).

Millay didn’t only write sonnets, of course. She wrote hundreds of poems in free verse and other forms. I want to offer here a few shorter and lesser-known poems, but honestly, I don’t know where to start. There are so many.

Not much has been written about The Plum Gatherer (as far as I can tell), a poem from Millay’s 1928 volume “The Buck in the Snow.”

The Plum Gatherer

The angry nettle and the mild

Grew together under the blue plum-trees.

I could not tell as a child

Which was my friend of these.

Always the angry nettle in the skirt of his sister

Caught my wrist that reached over the ground,

Where alike I gathered,—for the one was sweet, and the other wore a frosty dust—

The broken plum and the sound.

The plum-trees are barren now and the black knot is upon them,

That stood so white in the spring.

I would give, to recall the sweetness and the frost of the lost blue plums,

Anything, anything.

I thrust my arm among the grey ambiguous nettles, and wait.

But they do not sting.

Millay was a naturalist. Like Dickinson, she knew her plants very well, both cultivated and in the wild. Plum trees and stinging nettle grow in the same soil in the northeastern U.S., and her description of nettles growing under the blue plum-trees is accurate and certainly from her Maine childhood.

The poem’s speaker is an adult looking back to childhood when, while out gathering plums, she never knew which nettles were “angry” and which “mild” beneath the tree. But this poem is not merely a revery. It is a lament. The final stanza is in the present tense, and the plum trees “are barren now,” and the speaker would give “anything, anything” to be able to reach for plums “among the grey ambiguous nettles, and wait.” But the nettles no longer sting. Life once offered plums and stinging nettles, sweet plums and broken plums. Now it offers nothing. She would give anything, anything, to have the richness, the good and the bad, back again, and to “thrust” herself once again into life’s deep mix.

This is poignant, beautiful, and sad. Millay had a hard time with aging, due in equal parts to youthful self-identity and multiple health problems. This poem would have been written in her early middle age, when life’s peak vitality begins to show its first signs of waning.

I think that Millay’s detractors would see the poetic line “anything, anything” as the kind of histrionic, sentimental, and womanly writing they disdained, as if it were the back of a woman’s gloved hand across the forehead. If so, I beg to differ. I like it. It is real. It makes me read the line a certain way, as Robert Frost once said of the sound of the simple sentence You, you in a poem. “It is so strong that if you hear it as I do you have to pronounce the two you’s differently.” (RF Letter, Dec. 1914). “Anything, anything.”

I prefer Millay’s plums to the ones William Carlos Williams stole from the fridge.

Here’s a second poem. Of all the immortal things to be said about Beauty, “I am waylaid by Beauty” is among the finest.

Assault

I.

I had forgotten how the frogs must sound

After a year of silence, else I think

I should not so have ventured forth alone

At dusk upon this unfrequented road.

II.

I am waylaid by Beauty. Who will walk

Between me and the crying of the frogs?

Oh, savage Beauty, suffer me to pass,

That am a timid woman, on her way

From one house to another!

The speaker is waylaid by Beauty, reduced to timidity by its savagery. Beauty is savage. And Love hurts. I, too, am waylaid by Beauty, by this very poem. I won’t offer an interpretation and instead ask you, dear reader, to read it again. Take what you can from it. It is short. Read it now, and again tomorrow. You may wonder: why a year of silence? What is the crying of the frogs to her? Where is she going, why from house to house? Imagine the answers, but you don’t need them to tap into the intensity of the expressed feeling. This is the heart of poetry.

Finally, here’s a poem not by Millay, but by me. It is my sad and sorry contribution to the sonnet love genre.

Loving Millay

last night I slept with edna st vincent millay

her book of poems lay on my chest

like a gentle hand with fingers splayed

a rhythmic caress stirred the unstressed

coo and purr of vincent’s words

uncurling as I fell through

the love-lost years where we heard the birds

at steepletop and sipped the sapphic brew

spilt upon the pages of her book

of poems stained with pencilled love

tracing the Beauty bare that shook

the midnight air til I - sated - reached above

to dim the light, drowsily fingered the spine

of my millay as we slipped into the dark divine.

Here’s Millay’s home in upstate New York, to which she decamped from the wilds of Greenwich Village, NYC, and spent the rest of her life gardening, partying, loving her husband (and others), and writing poetry.

Beautiful words… and photography.