Very few of us will lead rich posthumous lives. Our candles will burn briefly and be snuffed from living memory within a generation or two. Even the extra candlepower provided by social media won’t expand our worldly presence. Our little haloes of light are unlasting.

For the small percentage of humanity that creates art, their names may outlast their lives if their art is good enough and influential. Apart from some avant garde outliers (think Fluxus), every work of art wants to be seen, persist, and withstand time.

Of all the arts, poetry is the one with the power to directly express that drive. Since the time of Horace, poets knew their poetic lines could persist, even as grand monuments and heroic deeds succumbed to the erasures of Time. The very acts of the gods are doomed to be forgotten, unless they are memorialized in poetry and song. After all, Erato, the muse of lyric poetry, was the daughter of Mnemosyne, the goddess of memory.

As the German Romantic poet Friedrich Hölderlin said, “poets establish that which endures.”

However, which poems make it into the pantheon, or in more contemporary terms into the anthologies, is not the result of some immutable law of merit or fairness. The history of poetry reflects the opinions of established critics and scholars whose theories of Great Poetry can confer honoraria or obscurity on working poets. But even those who achieve recognition in their time may find it fleeting. What one generation thinks is Great Poetry the next generation forgets.

Like emperors and their grand monuments, poetry is ultimately unlasting.1 Poems don’t die, but they do vanish into a state of cryptopoesis.2

Remembering Ruth Stone

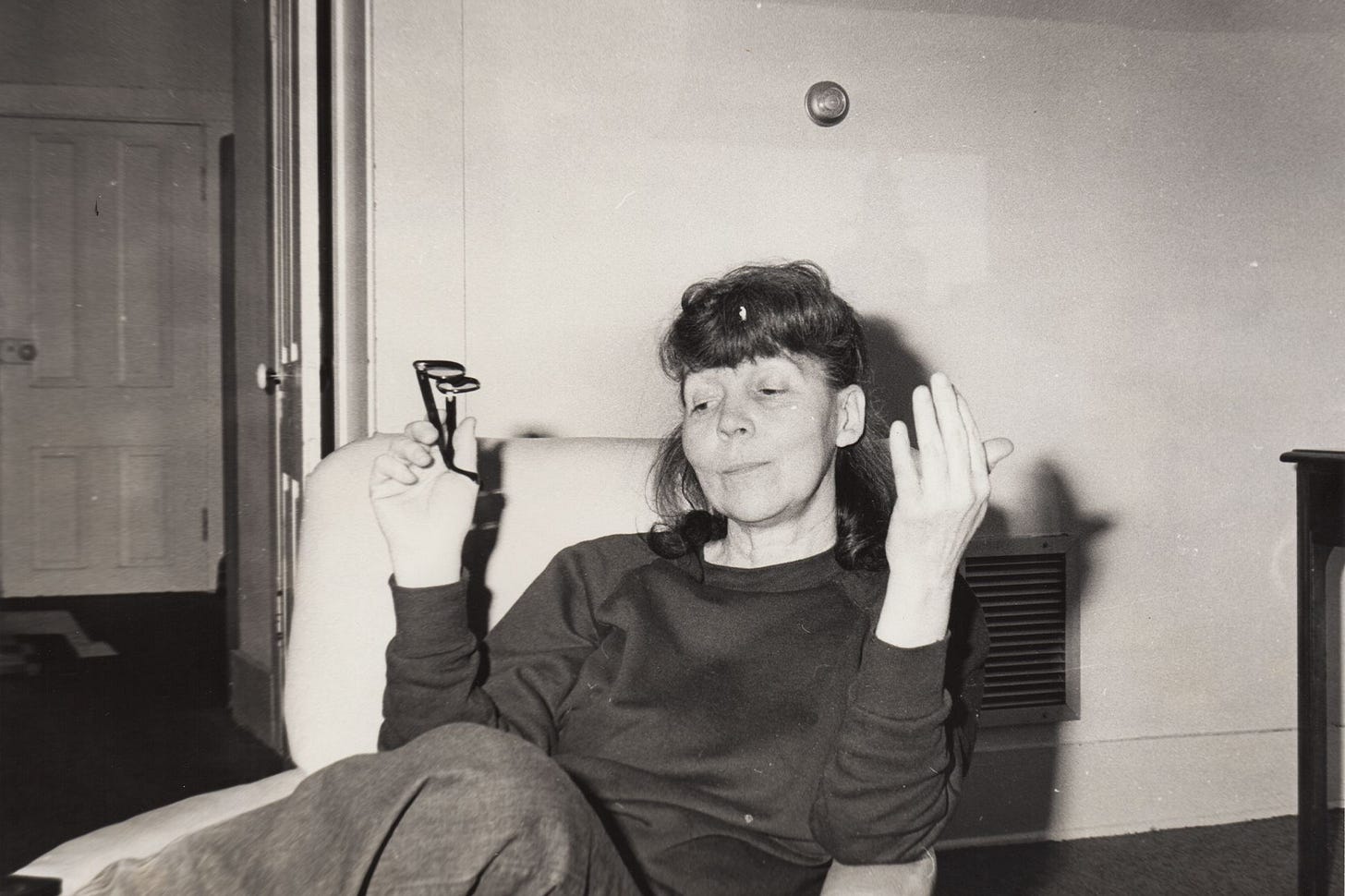

Ruth Stone was a poet who waited until late in life to achieve serious recognition. When the accolades came, Ruth was in her eighties. “They probably gave it to me because I’m old,” she laughed.

(Forgive the impertinence of calling her by her first name, but she seems more “Ruth” to me than “Stone,” and not using her first name would make her “Ruthless,” which she was anything but.)

She is gone now, and I fear she is in danger of being overlooked and forgotten. Ruth knew this is the fate of poets. “Poets come and go,/ like squills that bloom/ in the melting snow.,” she says in the poem “Fragrance.”3

Born in 1915 in Virginia, she went to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign where she met the blazing love of her life, a young poet and graduate student Walter Stone. They fell madly in love, and she immediately divorced her first husband (she had married at the age of 19), and married Walt in 1945. He was a poet of some promise, and together they moved to a farmhouse in Goshen, Vermont and raised three children (the first from her earlier marriage) while he was a professor of poetry at Vassar College.

Her life took a tragic turn in 1959, however, when Walter, on a sabbatical in London, hung himself by his tie in a London hotel closet.

She later said she never understood why he did what he did. It was incomprehensible. She knew they loved each other dearly, and she came to know his suicide was not an act against her but against himself, against his own personal darkness.

At the time of her husband’s death, Ruth was about to publish her first book of poetry, but the unreckonable tragedy derailed her career. Suddenly she was a single mother of three, deep in grief. While the first book (“In an Iridescent Time”) did come out in that terrible year of Walter’s death, she didn’t publish again until her 1971 (“Topography and Other Poems”). And then there was nothing for 15 more years.

Her immense grief could only be grasped by writing poetry. She stayed in the farmhouse in Goshen, raised the kids alone, and taught Creative Writing in various colleges around the country. And grieved.

In her poetic life she was relatively obscure, known mostly by other poets and several generations of students who were lucky enough to take her class. Her poetry was fierce, unsentimental, original, and deeply authentic, and her teaching was inspiring. In what was then a tight-knit poetry community others saw the promise in her work, and she won various fellowships that enabled her to continue. She was admired by the likes of Adrienne Rich, Sharon Olds, Sandra Gilbert, Edward Hirsch, and Toi Derricotte. But with only two published volumes of poetry, she was an admired but minor poet.

Her children grew, married, had children, and always supported her as she aged in her shambolic country house or as she traveled in her old white car to teaching jobs. Those one-year contracts at colleges around the country kept her on the move and, through her students, quietly expanded the soft halo of light she cast upon the literary landscape.

In these lean years it seems not to have mattered much to Ruth that her work was not widely acclaimed. She had children to raise, a family catastrophe to manage, and always more poems to capture out of thin air.

It was not until her later years that a great flowering of recognition occurred. She began publishing more actively after she turned 70. In 1990, at the age of 75 she became a tenured professor of English and creative writing at the State University of New York in Binghamton. And soon it was as if Fame had been gathering in the wings, waiting for a poignant moment to emerge.

In 2002, at the age of 87, she won both the prestigious Wallace Stevens award for lifetime achievement and the National Book Award for Poetry for her volume “In the Next Galaxy.” At the age of 92 she was appointed the Poet Laureate of Vermont, and in 2009 at age 94 she was a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize.

She died in 2011 at the age of 96, and soon the shouting dimmed. Acclaim, after all, is unlasting. There’s not a lot of posthumous room at the top.

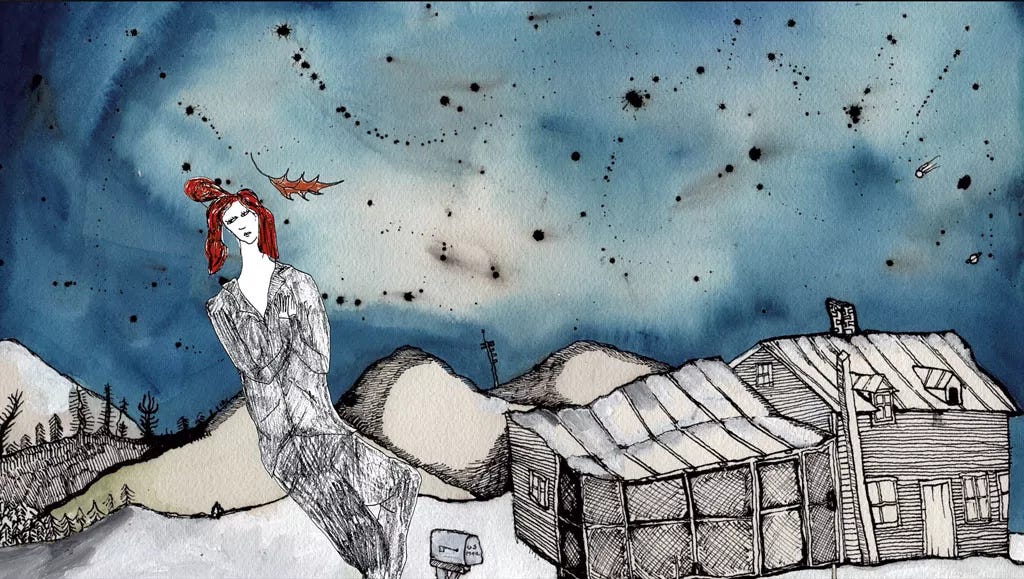

She’s gone, but not entirely forgotten, since her family is doing yeoman’s work to memorialize her poetry and make a literary destination of her unusual Vermont home. To this end, the family converted the place into the Ruth Stone House where Ruth’s literary and physical legacy persists and new poets gather for classes and workshops in a place once visited by Muses.

Visited by Muses? This is not entirely a poetic trope. Ruth had something of a mystical relationship with the act of writing. As she explained in an interview:

I’d feel and hear a poem coming from a long way off, like a thunderous train of air. I’d feel it physically. I’d run like hell to the house, blindly groping for pencil and paper. And then the poem would write itself. I’d write it down from the inside out. The thing knew itself already. There were other times when I’d almost miss it, feeling it pass through me just as I was grabbing the pencil, but then I’d catch it by its tail and pull it backwards into my body. Then the poem came out backwards and I’d have to turn it round.

Elsewhere she said the poem comes “like a stream alongside me. It just talks to me, and I write it down.” This strange experience is one she experienced in childhood and wrote about in “Fragrance,” mentioned earlier. In a home openly receptive to her creativity (her father often printed her childhood poetry on a Linotype machine), she would feel the poetic impulse “Like the sudden breeze / that pulls the petals/ from the honeysuckle.”

A brilliant documentary of Ruth’s life — “The Vast Library of the Female Mind” (I can’t recommend it highly enough; it will move you to tears of joy) — captures this strange magic when, in an instant of creativity at the kitchen table, Ruth’s hands are weaving a pattern in the air as if she is grabbing the words to write down.

She anchored herself in her poetry, the poet Major Jackson said of her, not just to process her deep grief over Walter but to offer the broader story of her life. She never stopped praising and honoring Walter, despite what he did, and she clearly never stopped loving him. The family survived and thrived — almost all of them becoming artists themselves — through the largeness and specialness of her spirit and her fidelity to poetry.

In the movie we see Ruth’s grown granddaughter going through papers strewn about a room where she worked. Poems were all over the place, in snippets of paper, on the desk, on the floor. Her granddaughter picks up what looks like a pad of sticky notes and begins reading a quickly jotted poem that ends when Ruth had to jot down someone’s phone number (if I remember correctly).

She wrote the poem and abandoned it. It was just a quick word from the Muse, until her granddaughter found those lost lines and brought them to the light. It’s a poetic fragment, unfinished, and not particularly important. But it reminded me of Emily Dickinson’s sister Lavinia finding that trove of hundreds of unseen poems that Emily had stored out of sight in her dresser drawer. Lost or forgotten poems can storm back to life and change the world.

The Poetry

More important than the biography is the poetry. Every page of it is infused with her life experience, small and large, but over and over the poems transcend her own experience. Joy and loss, memory and grief, the holiness in the mundane, aging, all of our universally-lived Big Issues are there, coming through in a poetic voice that is consistent, clear, and uniquely her own. She writes in a vernacular tone with irony, humor, wryness, candor, sadness, irreverence.

Which poems should I include here? Very, very hard to choose. There are so many good ones in “What Love Comes To: New and Selected Poems,” the 2008 volume that garnered Pulitzer attention the following year. At the risk of overemphasizing the issue of her age, she was 93 years old when the book, with its 68 new poems, was published.

This is the one that I ran across serendipitously on the internet that brought Stone to my attention. It grabbed me immediately.

Wild Asters

I am here to worship the blue

asters along the brook;

not to carry pollen on my legs,

or rub strutted wings

in mindless sucking;

but to feel with my eyes

the loss of you and me,

not in the powdered mildew

that spread spreads from leaf to leaf,

but in the glorious absence of grief

to see what was not meant to be seen,

the clusters, the aggregate, the undenying multiplicity.

I instantly liked that enjambment on the first line: “I am here to worship the blue”. Asters, as it turns out, blue asters, those bountiful providers of pollen and nectar. She is not like the bees who, in their work and worship of the flowers, carry pollen on their legs or beat their wings against the petals as they extract the sweetness they came for. She is here “to feel with my eyes/ the loss of you and me.”

This took me by surprise. First, the arrival of loss among the blue asters, a flower beloved by bees and butterflies. But also the idea of feeling the loss with the eyes. We don’t “feel with our eyes.” Our eyes are not receptors for touch. What she feels with her eyes is an interior feeling: she sees “the glorious absence of grief” in this place, and she sees what she and Walter were not meant to see together, which is, I think, the bountiful “clusters” of life in their “multiplicity” that outlived “you and me.” Sad, yes, but do remember the opening line: she was there to “worship the asters.” She was there to worship them on behalf of the two who were not meant to see them together.

Here is sad and poignant poem about love and memory from her 1999 book “Ordinary Words”:

1941

I wore a large brim hat.

like the women in the ads.

How thin I was: such skin.

Yes. It was Indianapolis:

a taste of sin.

You had a natural Afro:

no money for a haircut.

We were in the seedy part;

the buildings all run down;

the record shop, the jazz

impeccable. We moved like

the blind, relying on our touch.

At the corner of coffee shop,

after an hour's play, with our

serious game on paper,

the waitress asked us

to move on. It wasn't much.

O mortal love, your bones

were beautiful. I traced them

with my fingers. Now the light

grows less. You were so angular.

The air darkens with steel

and smoke. The cracked world

about to disintegrate,

in the arms of my total happiness.

She recalls their young lives — in 1941, Stone would have been 26 years old — when they were without money, without a plan, and in love. But their love was a “mortal love.” They didn’t know then that love was mortal and that the world would crack and destroy the “total happiness” they held so briefly in their arms.

In 1991, Stone wrote an entire volume of poetry in which she wrestles and fights and argues with her Muse about the death of her husband. His death, after all, was the ironic source of inspiration for so much of her work. These poems gather steam from one another, and reading just one loses something essential. But consider this one, number XLII, which captures something of the tone of the whole:

After thirty years

the widow gets smug.

”Well. I did it,”

she brags,

”with my own bare hands.”

The muse shrugs.

”Uh-huh. . .

Did what?”

The muse leads her to

a back stairway.

There is his undershirt

in an old trunk.

”Smell that,” the muse says.

The widow inhales his lost perspiration.

”You brute,” she whimpers.

The muse takes a bone

out of her arm

and knocks the widow senseless.

”She’ll never learn,”

the muse simpers.

I don’t want to give the impression that she only wrote about Walter and grief. She often wrote movingly of her daughters, Here’s a happier memory of life with Walter and the children:

Green Apples

In August we carried the old horsehair mattress

To the back porch

And slept with the children in a row.

The wind came up the mountain into the orchard

Telling me something;|

Saying something urgent.

I was happy.

The green apples fell on the sloping roof

And rattled down.

The wind was shaking me all night long;

Shaking me in my sleep

Like a definition of love.

Saying, this is the moment.

Here, now.

She was, also, a strong-willed feminist who understood the battle women faced in a male-dominated poetry environment.

Words

Wallace Stevens says,

“A poet looks at the world a poet looks at the world

As a man looks at a woman.”

I can never know what a man sees

when he looks at a woman.

That is a sealed universe.

On the outside of the bubble.

everything is stretched to infinity.

Along the black top, trees are bearded as old men,

Like rows of nodding gray-bearded mandarins.

Their secondhand beers were fun by female, gypsy moths.

All mandarins are trapped in their images.

A poet looks at the world.

As a woman looks at a man.

The poem was published in her 1999 book “Ordinary Words.” The Academy of American Poets held no grudge when, three years later, it awarded her the prestigious Wallace Stevens Award (along with its $100,000 prize. At the age of 87, she said she was stunned, humbled, and jubilant.

In what I think is the funniest, most sardonic poem about writing poems — a small genre that includes poems by Billy Collins and Marianne Moore — Ruth imagines the poetry business as a factory with a straw boss and a work force of oppressed poets. In five sections, “Some Things You’ll Need to Know Before You Join the Union” eviscerates the machinery of “Po-Biz” that pumps out poetry like cheap clothing in Third World countries. “At the poetry factory,” the poem begins, “body poems are writhing and bleeding.” An angry mob is hoping for jobs. In one room, they process political poems which “are packaged in cement./ You frequently hear them drop with a dull thud.” Other poems are “shipped out by freight car,” like cattle. “They will go to the packing houses./ The slaughter will be terrible. . ./ Their shelf life will be brief.” Others are being “stuffed to their limits.” Some explode, but “Most of them lie down and groan.” Finally, only a “nervous apprentice” is around as “a large poem/ seems to come off the assembly line.” And with the large poem done, it’s Po-Biz showtime for the apprentice:

“Get my promotion ready!

APR, the quarterlies,

a chapbook, NEA,

a creative writing chair,

the poetry circuit, Yaddo!”

Inside the ambulance

as it drives away

he is still shouting,

“I’ll grow a beard,

become an alcoholic,

consider suicide.”

A hilarious send-up of the hopes of countless poets . . . except . . . when you consider that mordant last line and remember her beloved husband’s demise.

There are many other poems I’d love to share, but you, dear reader, need to find them on your own. You’ll have to buy her book of collected poems since the internet doesn’t offer many for browsing. (Here are some.) Read “Against Loss” which movingly and surprisingly combines an encounter with the immortal jazz great Billie Holiday and the final words of Matthew Arnold’s immortal poem “Dover Beach.” Or her lament - or perhaps it is a prayer - for her daughters in “Seed”: “my Indian corn, my maize,/ my seeds for a ruined world’/ Oh my daughters.”

The poem “Metamorphosis” enters into the movie when the family aids Ruth in reciting it by reciting it together when Ruth falters. (You can also find Ruth reading it on YouTube.) It is her epilogue poem, a great looking back at a life of “unbearable longing,” and a lovely place to end this essay.

Now I am old, all I want to do is try;

But when I was young, if it wasn’t easy I let it lie,

Learning through my pores instead,

And it did neither of us any good.

For now she is gone who slept away my life,

And I am ignorant who inherited,

Though the head has grown so lively that I laugh,

“Come look, come stomp, come listen to the drum.”

I see more now than then; but she who had my eyes

Closed them in happiness, and wrapped the dark

In her arms and stole my life away,

Singing in dreams of what was sure to come.

I see it perfectly, except the beast

Fumbles and falters, until the others wince.

Everything shimmers and glitters and shakes with unbearable longing,

The dancers who cannot sleep, and the sleepers who cannot dance.

I’ve used the word “unlasting” three times with intended irony. The word “unlasting” itself demonstrates its meaning: it didn’t last. The Oxford English Dictionary says it is obsolete, making its final short-lived appearance in the early 1600’s and then vanishing. Its contemporary synonym “dureless” (opposite of “enduring”) followed it out of use. Even supposedly deathless words have a vanishing point.

I made this word up. In the field of biology, cryptobiosis is a phenomenon where certain living creatures enter into a state of existence that is neither living or dead. Through dessication or becoming frozen, they stop all metabolic activity and show no sign of life, and their cellular make-up may even begin to degrade. This can persist for thousands of years (in one instance, 48,000). But introduced to water or light, they spring back to a full life. A lost or unread poem will become cryptopoetic. It is neither alive or dead until someone finds it, brings it to the light, and reads it. If it’s any good, it will instantly spring to life.

To my eternal delight, “Fragrance” has my favorite opening line in all poetry. It is simply this: “Edna St. Vincent Millay—”.